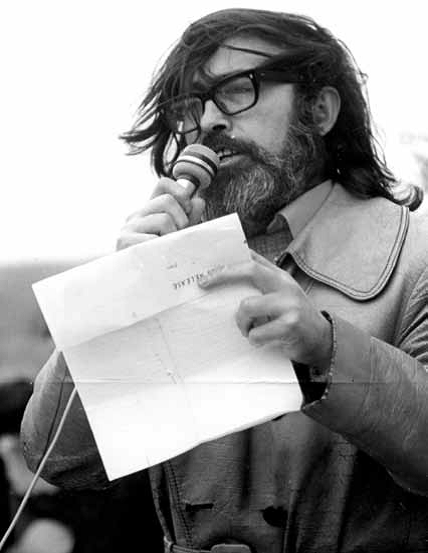

Teacher and troublemaker, Des O’Hagan was a founder of the Civil Rights campaign and a giant of the Republican movement. Ultan Gillen recounts an unusual life.

The death of Des O’Hagan, the Marxist intellectual, author, polemicist, and veteran Workers’ Party activist, on 5th May 2015, brought to a close a remarkable life devoted to the cause of the working class in Ireland and around the world. A man who personified the Leninist dictum, “Agitate! Educate! Organise!”, Desi was also a loving husband and father, a Gaelgeoir, a man of great wit and charm, a smoker, a fan of the art of distillation, a dab hand in the kitchen, and a leading member of what he described as “the punters’ wing of The Workers’ Party”.

Des was born in Belfast into a family with a strong left-wing heritage. His grandfather, Michael McKeown, was a prominent member of the dockers’ union during the 1907 Belfast dock strike led by Jim Larkin. His mother’s family lived beside James Connolly in Belfast, and Connolly was a family friend. Desi’s mother had a profound influence on him. A great reader, she was herself a revolutionary republican, and he often recalled a Christmas night when his mother and uncle were discussing the Spanish Civil War, unaware that young Des was hiding behind the sofa. His uncle, a devout Catholic, denounced the killings of clergy by Spanish republicans; his mother, herself equally devout, retorted that they must have deserved it.

It was to his mother’s influence that Des ascribed his decision to join the Fianna aged 13, initiating the political activism that would span the next seven decades. He joined the IRA aged 15, lying that he was 16 (that was not the only army he joined, and he later served in the Irish Army’s Irish-speaking unit). He always laughingly recalled the opinion of the vice-president of St Malachy’s College: “O’Hagan, I predict you will be hung by the time you are 21”.

His politics then were very different to what they would become, reflecting the narrow, militaristic nationalism that was then regarded as republicanism. Des was involved with the splinter group Saor Uladh. From 1956, he served four years in Crumlin Road gaol for trying to break out a prisoner from the nearby Mater Hospital.

After his release, Des went to England and studied sociology at the London School of Economics. His reconceptualization of revolutionary politics led him to embrace Communism. Well-regarded at LSE, he had offers from three departments to undertake a PhD but returned to Belfast for family reasons.

Back home, Des found a job teaching education at Stranmillis College for trainee teachers. A charismatic lecturer, his students appreciated his efforts to expose them to new ideas and get them thinking about the class dynamics of Northern Ireland’s education system. In the late 1960s, one of those students, Norma McKnight, introduced Desi to her sister Marie, who shared his politics and with whom he would share his life until her death in 2008.

Des also re-involved himself in the local political and cultural scene, making contact again with old comrades like the fellow Gaelgeoir Liam McMillen. For a time a member of the Communist Party Northern Ireland, Des was a founder member of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. The struggle for democracy and civic equality was central to his political ideology and activity for the rest of his life. But Des knew that civil rights were about more than that, with jobs and housing just as important. As he stated later, “One Man, One Vote (in the gendered language of the time) was a good slogan; One Man, One Vote and One Job was a better one”.

With others, Des played a prominent role in organising the demonstrations that put the question of civil rights in Northern Ireland on the international stage. Witnessing reactionary unionism’s refusal to grant basic civil rights, Des rejoined the Republican Movement, as Liam McMillen had been asking him to do for some time. Des quickly became a leading member and a driving force in the process that transformed the Republican Movement into the Workers’ Party.

His nickname was acquired when Canon Murray of St Peter’s Catholic Cathedral denounced him from the pulpit as a Communist and the Devil

An inspiration for those committed to secular, socialist politics, Des was a thorn in the side of its opponents. His nickname was acquired when Canon Murray of St Peter’s Catholic Cathedral denounced him from the pulpit as a Communist and “the Devil” (pronounced locally as the Divil).

On the first day of internment, 9th August 1971, soldiers kicked Desi’s front door down, and dragged him from the house. In Girdwood barracks, Desi was kicked and beaten, and put up against a wall as soldiers cocked their rifles, causing another internee who thought he was going to be shot to faint. He was protected from further abuse first by a soldier and then a warder. He was interned for a year and a day, but continued his political activity, organising a NICRA branch in Long Kesh and being active with the Republican Clubs there. His political lectures delivered to internees and the debates he conducted there persuaded some to abandon sectarian nationalism for socialism.

During internment, Des wrote the famous Letters from Long Kesh, which were smuggled out by Marie and ran in the Irish Times for six months in 1972, and which were republished by Citizen Press in 2012. The Letters tackled subjects ranging from the cold, mice and absurdities of life in the internment camp to Bloody Sunday and sectarian murders, as well as the suffering of the internees and their families outside.

Pressure from Stormont meant that Des lost his post at Stranmillis, and he became a full-time political activist on his release. Appointed National Education Officer for Official Sinn Fein, he took over the running of the Party school at Mornington, county Louth. His gift for making complex ideas simple and his ability to see problems at the human level made him perfect for the job.

It was Desi who encapsulated the Workers’ Party strategy in Northern Ireland in the slogan, Peace, Work, Democracy and Class Politics, and he played an important role in developing the idea of a Civic Convention and a Bill of Rights as a means of restoring devolved government. He recognised no boundaries among workers – his target audience was the entire working class, regardless of background. He was among those most responsible for making the Workers’ Party the strongest critic of sectarianism in Ireland, and at the forefront of supporting policies like integrated education.

As noted by his youngest son Aedan at his funeral, Desi’s application of Marxism was rooted in his favourite quote from Marx: “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.” He was a firm believer in the need to raise class consciousness, and he used his position as editor of Party publications such as the United Irishman and Workers’ Life to do so. He was also a keen proponent of cultural struggle, and was prominent in the organisation of the Belfast Workers’ Festival.

Desi played a key role in forging the Workers’ Party’s links with the socialist states. He was not blind to their faults, but he always recognised their achievements, not least in defeating Fascism in World War II and supporting national liberation struggles, and in raising living standards and women’s liberation. At his funeral, his oldest surviving son Donal (his oldest son, Ciaran, from an earlier marriage predeceased him), eloquently told Desi’s life story by speaking the names of places of significance in his life. Moscow and Tokyo featured just as did Drogheda and Downpatrick, telling the tale of a true internationalist.

As Desi had played a key role in the process which brought electoral success for the Workers’ Party in the Republic during the 1980s he also was on the front line in the early 1990s battle to save the party from being destroyed by the actions of those who established Democratic Left.

In February 1992, he identified exactly the real aim of the faction led by Proinsias de Rossa. “Undoubtedly the most significant and damning aspect of these proposals is the clear abandonment of a class viewpoint.” The next year, in 1993, Des wrote the major theoretical statement, The Future is Socialism, which analysed the fall of the socialist states, the betrayal of socialism by many former Communists, and predicted the rise of the right-wing form of social democracy soon to be called Blairism, while demonstrating the ongoing importance of a Marxist analysis in a changing world.

In 1998, for the bicentenary of the United Irish rebellion, his The Concept of Republicanism reiterated the fundamental factors that made up republicanism in the revolutionary spirit of Tone: republicanism had to be democratic, secular, socialist, and internationalist.

Des continued to be active on the ground as a local community activist and an election candidate for the Workers’ Party into the new century. Although he took a step back in recent years, he remained a committed Party member, and a valuable source of inspiration and advice.

Des O’Hagan was a man fired by a humanistic vision of a better, more democratic and more equal society. His hopes for a better world shaped his whole life and dictated his work as an activist, theorist and educator (and explained why he was banned from the United States, something he considered “a great compliment”).

He leaves a legacy in his family, his writings, and in the inspiration he has provided to his comrades who seek to follow in his footsteps.

Des O’Hagan (29th March 1934 – 5th May 2015)