The causes, course and consequences of the First World War were imperialist. Don’t let arguments about poppies obscure that, writes Padraig Mannion.

To wear a poppy or not to wear a poppy? This is a question which at this time of year religiously reappears in the letters pages of our national newspapers. While this debate might be entertaining, and it may even throw some light on the state of Anglo-Irish relations, it totally avoids dealing with the true nature of the First World War: that conflict was, unarguably, an imperialist war.

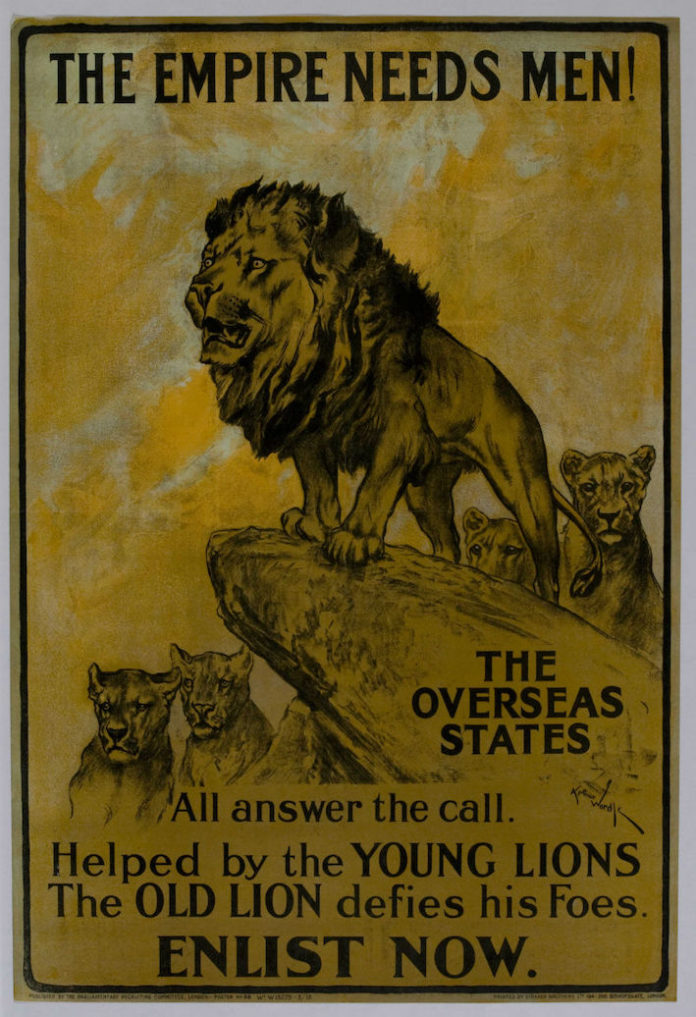

Between 1914 until 1917, the First World War was fought between two alliances comprising the five big European empires as well as the emerging powerhouse that was Germany. Even in 1914, as this Great War commenced, it was misrepresented (especially by the British empire) as a war against the “Hun tyranny” in defence of ‘poor defenceless Belgium’. No mention, of course, of Belgium’s massive African empire centred on the Congo, an empire which was a byword for barbarism, cruelty and human degradation. There were lots of appeals to ‘the empire’ but little talk of ‘imperialism’. No mention of the Anglo-French anger felt because Germany had begun to erode their traditional trading fiefdoms in Latin and Central America, particularly in Argentina and Paraguay. No mention of British imperial anxiety that close German-Ottoman cooperation in the developing railway and oil industries could pose a threat to Britain’s Indian empire.

First World War armies were enormous. France and Britain had, between them, over seventeen million mobilised troops. How was this possible from a combined total population of just over eighty seven million people? This would give, approximately, a combined male population of 43 million, and a total eligible male population of around 25 million when those deemed unfit for military duties are excluded. This would mean that 37% of all males, or an incredible 70% of all eligible males, were in those two armies.

How was this possible while maintaining agriculture and industry at the same time?

It wasn’t possible and it didn’t happen. Because more than four million of those troops came from the colonies. Ah yes, the Canadians, the Australians, the New Zealanders and the white South Africans. But they only accounted for a little over one million troops. What of the other three million?

The UK had more than one and a half million Indian soldiers, who mostly fought against the Ottoman empire in Egypt and the Middle East, including Mesopotamia. Indian soldiers also fought with the British in the German colonies of East Africa, now Tanzania, but the bulk of the UK troops here were African. The UK also had about 135,000 African troops involved in the very protracted East-African war, along with another one million, mostly press-ganged, African labourers, porters, cooks and navvies. The death-rate among this vast force was never officially recorded but is estimated at between 20% – 25%.

France also plundered its colonies for troops and other workers. Between its African and Indo-Chinese territories it recruited an extra half million troops to add to the existing 90,000 ‘troupes indigènes’. Unlike the British, many of the French African troops fought on the Western Front. France also recruited a vast number of workers from Africa and Indo-China to maintain its domestic agriculture and industry during wartime. For example, it is estimated that at least 50,000, mostly Vietnamese, workers were recruited into France for the duration of the war.

France and the UK also combined to use their concession ports to ‘recruit’ over 100,000 Chinese labourers as part of the war effort. These badly paid, badly fed and generally ill-treated men performed some of the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs behind the front lines as well as in munitions plants and in transport. This, despite China being, in theory at least, both independent and neutral. For the Chinese it is another part of the century of historical humiliation.

1918. The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. The First World War officially ends. The Tsarist, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires have been swept away into the dustbin of history. But the Belgium, Dutch and Portuguese empires remain intact.

Simultaneously, the UK and France, substantially expand their empires. South of the Sahara, France annexes Togo and the bulk of Cameroon from Germany, while the UK grabs Tanzania. South Africa with the blessing of the UK government, grabs Namibia.

In North Africa the previous Ottoman possessions of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt are grabbed by France, Italy and the UK respectively. In the Middle East, as part of the secret 1916 Anglo-French Skyes-Picot Agreement, France took control of Lebanon and Syria while the UK took control of Mesopotamia, modern Iraq and Palestine. Palestine was then subjected to the secret and duplicitous Balfour Declaration of 1917.

The carve-up of the Ottoman empire was officially recognised in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. This gave international recognition to the newly created state of Turkey within borders which have remained reasonably constant to the present time. Anatolia remained part of Turkey as opposed to being a separate state as originally demanded by the UK and France. The pay-off for this was the concession of Mesopotamia /Iraq to the UK, the ceding of all Turkish claims to Iraqi oil, and the transfer of all pre-war and war-time German concessions in Iraq to the UK. This allowed the UK to have a guaranteed oil supply for both its home market and for its far-Eastern empire. Equally important for the UK was that the deal guaranteed an oil supply for its far-flung armies and navy.

Sixty five million European troops took part in the First World War. Over nine million were killed and many more millions injured, some permanently. Civilian casualties were not recorded but are estimated in the region of six million deaths. So, however we wish to remember Irishmen who fought in the conflict, we must recall that, whatever their individual motivation, they were mere pawns in a vast, life and death, inter-imperialist struggle that was, for the first time in recorded history, truly world-wide.