Human rights and the United Nations: wasn’t the purpose to create a new international human rights system, a potential legal panacea in the aftermath of the Second World War, promulgated by an organisation of the many, not the few?

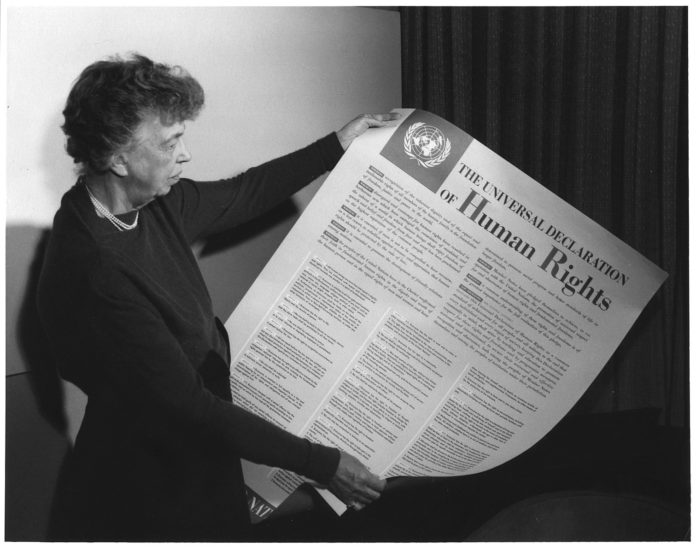

The creation of the United Nations (UN) on 24 October 1945 and the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) on 10 December 1948 are landmark events in the international legal system.

Elsa Stamatopoulou, former Deputy to the Director of the New York Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, spelled out that: ‘(…) the UDHR was a breakthrough and a revolution in international relations and has remained a continuing source of inspiration since 1948. It is a living document in United Nations practice, by now part of international customary law. The United Nations has, through its history, held countries responsible under the high standards of the UDHR, whether they were United Nations member states or not.’

In the same vein, Stephen Marks writes that: ‘The principal institutional framework for furthering human rights in the world community is the United Nations, the only intergovernmental structure with a general mandate for realising all human rights in all countries.’

The modern human rights project, however, is inherently the brainchild of the Western hemisphere in order to further its liberal values and a neoliberal project. It is a neocolonial endeavour with the UN as the custodian of this very hegemonic project.

Third World elites – such as scholars, activists and politicians alike – have assisted in this endeavour to usher in a heyday for liberal democracy and free markets. In consequence, we ask the following question: how can the international human rights regime aid and assist a counter-hegemonic narrative while the United Nations serves as a guardian of justice for the many, not the few?

The manipulation of a liberation promise

The UDHR is widely considered as a milestone under international human rights law: the first document of universal and moral appeal. It is, however, the view of this author that the human rights project, however, is manipulated and corrupted.

The UDHR was a legal battleground between different ideologies: religious, economic, political and colonial.

To this end, Jessica Whyte’s book ‘The Morals of the Market’ offers an interesting insight into the history and divergences during the drafting procedures of the UDHR. She details the political animosities that ensued at the drafting process of the UDHR, with different actors, from Western nations and the Soviet Union adamant to submit the law to a particular worldview.

It became part and parcel of the hegemonic project in the Gramscian sense: a mass of people was willingly submitting to a system which left them at the same time alienated and disempowered and it is the law that secured the consent.

The United Nations, to this end, provides the forum for the metamorphosis of old to new humanitarianism, as human rights became the comforting pretext for the neoliberal project and Western hegemony. International human rights law is not only Western made law: it is the law to civilise, recalibrate, reconfigure and restructure the global order and the Global South in particular.

Yet, international human rights law was widely considered by Western mainstream scholars and politicians to be a liberating vehicle of international law amid decolonisation. International human rights law was seen as the legal weapon to challenge and remedy colonial injustice. To this end, Anthony Anghie writes: ‘The international human rights law that emerged as a central and revolutionary part of the United Nations period offered one mechanism by which Third World peoples could seek protection, through international law, from the depredations of the sometimes pathological Third World state.‘ Here, the UDHR was the direct reaction to the horrors of Nazism and fascism, as Charles Malik had stated at the drafting stage of the Declaration.

Nonetheless, as Aimé Césaire has noted in his ‘Discourse on Colonialism’, the white Christian bourgeoisie tolerated Nazism before it was inflicted upon them. They, white Christians, ignored and legitimised Nazism, they closed their eyes to the horrors that were inflicted upon non-European peoples in Congo, India, Brazil and elsewhere – until they were harmed themselves.

Human rights imperialism, third world elites, and so called- liberation movements

One often enunciated claim is that the UDHR is truly universal as some drafters of this very document came also from the Global South and that they diversified and reconciled opposing cultures.

The vigorous proponents of the international human rights regime and the UDHR like Steven L.B. Jensen stress that the Global South had a key role to play at the negotiation tables: Global South representatives like the aforementioned Charles Malik from Lebanon, Carlos Romulo from the Philippines, Dr. Peng-chun Chang from China or Hernan Santa Cruz from Chile come to mind. Moreover, Susan Waltz explains that the UDHR is a heritage that all can rightfully claim, as it is a product of common effort.

Notwithstanding this fact, one cannot ignore an important point: Malik, Romulo and even Santa Cruz and Chang were Westerners from the non-Western world. All four have had privileged, aristocratic family backgrounds (in the case of Malik, Romulo and Santa Cruz being also of Christian faith) and all with enhanced Western education.

It was colonialism that allowed the members of the Third World elite to sit at the table with the former colonial masters and discuss a new international human rights regime – much in the way and manner how the former colonial masters wanted it to be.

Colonialism might have ended, but not the colonial state. Third World elites aided, abetted and assimilated the Western hegemonic project, and, speaking with Frantz Fanon, rose to power by mimicking the colonial and neo-colonial masters.

While the use of human rights language creates diplomatic legitimacy for governments, favourable conditions for trade and allows to enter the UN, the same organisation which is reproducing the colonial hierarchies where ‘sovereign political spaces are thus replaced by a global human rights space in which force can legitimately be used’ – only then to entrench and conflate legitimacy and hegemony of Western states.

In the end, Third World elites and self-entitled ‘liberation movements’ are being agents of human rights imperialism.

Human rights, eventually, is a means to an end: accessing sovereign space where economic and political influence is creating neo-colonial dependencies. Against this background Anna Spain Bradley has ascertained that the United Nations Charter and the UDHR assisted in the making of the new post-war world order. And she goes further to state that this post-world order maintained the racial superiority of Western states and the United Nations was to no avail to overcome this racial superiority.

With the same rigour, Makau Mutua explains that the ‘(…) human rights corpus is essentially European. This exclusivity and cultural specificity necessarily deny the concept of universality. The fact that human rights are violated in liberal democracies is of little consequence to my argument and does not distinguish the human rights corpus from the ideology of Western liberalism; rather, it emphasises the contradictions and imperfections of liberalism.’

The United Nations, as noted elsewhere, is trapped within the prescriptive parameters of Western liberal democratic governance and of free market values, while human rights law has become the undergirding fundament to support the Western hegemonic post-war world structure.

Alas, where do we go from here? With the UN at 75 and the UDHR at 72, it is the utmost time to pause, reflect and take stock of our fought battles. First, human rights are a Western construct with limited applicability to the non-Western world. Second, human rights aid the hegemonic construct. To this end, thirdly, human rights need to be decolonised. While international human rights law is portrayed as universal endeavour, as Antonio Gramsci has outlined, the establishment relies upon a dominating worldview of requiring universalisation, naturalisation, and rationalisation. This universalism is an overarching view of an elitist formation which sees parochial interests as common and vested goals of all people.

Balakrishnan Rajagopal sketches out that we need to stay engaged in counter-hegemonic resistance. He states: ‘A fundamental requirement for a counter-hegemonic international law is to develop a critique of the fetishism of institutions.

This is important for two reasons: first, to prevent an institutionalisation and consolidation of hegemony; and second, in that process, to prevent dissipation of much of the resistance to it.’ Similarly, we should not maintain and foster a fetishism for human rights law as the centre of a liberal law.

Human rights deprives, in effect, the ontological value of human beings. A true universal declaration of human rights is ‘flourishing from an organic, grassroots, localised and non-elite-led movements within existing nation-states.‘ Moreover, we need to introduce reparative justice and indigenise law. This is the counter-hegemonic response. The universal validity of human rights is one that was devised in the ‘corridors of power in the Global North, (which) suggest the arrogance of their advocates and their inability to meaningfully consider the perspectives of the most vulnerable individuals.’

We need revisit laws or frameworks in their diversity, which are trans-generational, and an omnipresent knowledge from the past which holds value in today’s world.

If we do so, that will give us a reason to celebrate in the future.