In February 1917, a popular uprising in what is now St Petersburg led to a provisional administration replacing the Tsarist order. Some kind of reformist government was in the offing. Lenin’s vision in The State and Revolution, responding to the turbo-charged atmosphere of change and politicisation sweeping the country, was incendiary. He wrote of the imperative to smash the bourgeois state and inaugurate a new communal form of social existence. Other Bolshevik leaders did not support his call for another revolution but Lenin sensed his country’s extraordinary capacity for deep-seated change.

Saying he was the spark that lit the October 1917 Revolution uses the metaphor also employed for the title of the samizdat newspaper – Iskra (Russian for ‘the spark’) – that Lenin helped establish in Germany in 1900. Pressure from the authorities required a change of location for the paper’s operations. Lenin chose London.

He made six visits to London and each of them is traced, with an engaging blend of scholarship and storytelling, in The Spark That Lit the Revolution: Lenin in London and the Politics that Changed the World It details where Lenin stayed, the three congresses of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) he attended in the city, some favourite haunts and the place where Iskra was printed. Self-conducted London walking tours with this book in hand suggest themselves as a rewarding way to spend some time in London as most of the addresses are within walking distance of one another.

Henderson’s book concentrates on new archival finds and previously unpublished materials. Much of what he uncovers is fascinating and valuable information, like the pub above which delegates met in secret for the RSDLP’s third congress in 1905. London was a favourite destination for Russian emigrés from 1890 onwards and Tsarist agents were busy trying to track their movements. Lenin was not alone in needing to use false names to disguise his identity. Dr Jacob Richter, as he called himself, was a voracious reader at the British Museum’s reading room. Indeed, the British Museum used to display his letter of application in that name for a reading ticket. His landlady pronounced the ‘ch’ as in ‘rich’ (not the German pronunciation as in ‘loch’); ironic considering his lifelong disregard for material wealth.

Henderson also provides a link to a documentary made in 1962 by a Soviet team in London for the sixtieth anniversary of Lenin’s first arrival in the city. The film’s attention to visual evidence makes it precious and highly watchable even though some of it is in Russian.

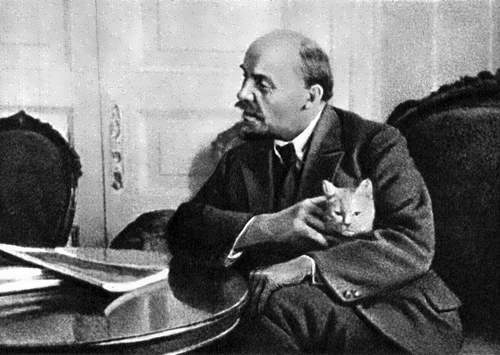

Another anniversary, arising from Lenin’s year of birth, has prompted Lenin 150 (Samizdat), a collection of writings and photographs that explore the political footsteps of Lenin worth following today. The contributors are an exhilaratingly mixed set of activists and academics and they write in various styles, from the lyrical and personal to the discursive and theoretical. The book’s origins can be traced to Kyrgyzstan – home to more surviving Lenin statues than anywhere besides Belarus – but its spirit is internationalist and its laudable regard for approaching Lenin from different perspectives is even more pronounced in its second edition. As a witty, relevant, inspirational and superbly sane collection of words and pictures, this is a book that requires two copies: one to keep and the other to present to a friend as a gift.

Lenin 150 mentions the praise for the 1916 Easter Rising expressed by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Richter’s real name), one example of the book’s ability to challenge hackneyed portrayals of Lenin as obsessively dogmatic and inflexible. When a leading fellow Marxist dismissed the uprising in Ireland as merely a peasant-based ‘putsch’, Lenin ridiculed the implication that revolution will follow a prescribed order of events: ‘So one army lines up in one place and says, “We are for socialism,” and another, somewhere else and says, “We are for imperialism,” and that will be a social revolution!’ Lenin was no romantic anarchist but neither did he believe there was a political recipe that could be followed which would guarantee success.

After February 1917, Lenin did not wait for some preordained moment when the time would be ripe for action. Thrown into an open situation created by contingent circumstances, he took a risk when others advised caution. As Slavoj Žižek observes in Lenin 150 – drawing a telling comparison that contrasts Collins with de Valera – an authentic political agent possesses this ability. Part of Lenin’s greatness, he goes on, was his persistence in trying to make the best of what he knew was an impossible situation after the forces ranged against Bolshevism launched a destructive civil war.

–

The Spark that Lit the Revolution: Lenin in London and the Politics that Changed the World, by Robert Henderson, is published by Bloomsbury

Lenin 150, edited by Joffre-Eichhorn, Anderson and Salazar, is published by Daraja Press.