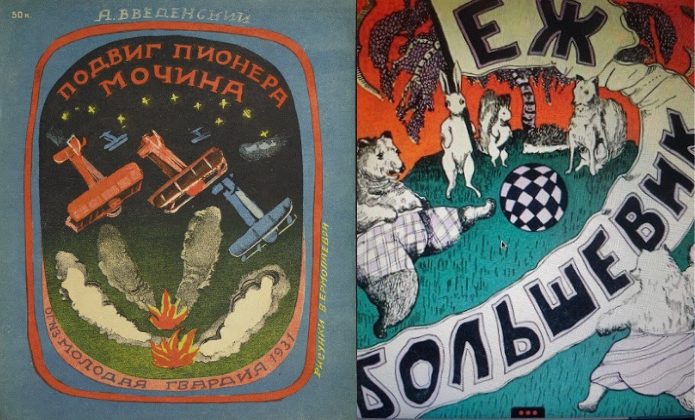

Above are cover images for Mochin the Pioneer’s Heroism, a story about a Young Pioneer helping the Red Army, illustrated by Vera Ermolaeva, 1931. And to the right, The Bolshevik Hedgehog in which a “worker hedgehog” takes on a “brutish Tsar boar”, after the latter prevents the hedgehog and his inter-species comrades from playing football. Thus, the noble hedgehog leads woodland comrades through the forest chanting “Eternal freedom to the feral people,” to depose their oppressor and play football once more.

Children in the Soviet Union were cherished by society and the Party. After all, children held the key to and promise of a socialist future. A key figure in the cult of childhood was Pavlik Morozov, a 13-year-old who reported his father for selling forged documents to bandits. Pavlik and his younger brother were brutally murdered by his own grandfather, grandmother, and uncle in retaliation, leading to much public outcry and a martyr status that saw statues erected in his honour across the Soviet Union.

From the earliest days of the Communist state, there was a reverence for childhood. Partly, this was a practical concern. Street children were numerous in Tsarist Russian and that issue was exacerbated by the conflict of the Bolshevik Revolution and the famine of 1920 and 1921.

In order for the international Marxist Revolution to succeed, these social problems had to be addressed and children had to be well-educated, both academically and politically. The Communist Party formalised a cult of childhood through youth organisations including the Komsomol, Young Pioneers, and Little Octobrists.

It was a cause that was close to Lenin’s heart. Outlining the Tasks of the Youth Leagues in Bourgeois and Communist Morality, Lenin postulated that: “…We need that generation of young people who began to reach political maturity in the midst of a disciplined and desperate struggle against the bourgeoisie. In this struggle that generation is training genuine Communists; it must subordinate to this struggle, and link up with it, each step in its studies, education, and training.”

In Small Comrades: Revolutionising Childhood in Soviet Russia, 1917-1932, a 2001 book by Lisa Kirschenbaum, the author outlines how kindergarten was used to further the Communist cause. This ideological education is evident in the many wonderful children’s books found throughout the history of the Soviet Union.

Children’s literature in the Soviet Union could, according to a 1976 analysis in the Laguage Arts Journal, by Miller, Williams and Williams, be divided into four categories.

Firstly, stories based on old tales and folklore, eg tales from Klylov, an 18th century satirist whose animal fables – The Raven and the Fox, The Wolf and the Lamb – are the equivalent of Aesop’s tales in the Anglophone world. Secondly, there were simplified adaptations of the great works of Russian literature. Thirdly, there were original and topical works for children.

The frankness and lack of condescension in these publications is striking. These books could offer straightforward, all-ages accounts of Party policy, including such books as: The Five Year Plan (1930), How the Beetroot Became a Sugar (1930), and 80,000 Horses (pictured above) which gave a thrilling account of the Volkhov Hydroelectric Plant.

A fourth strand of literature translated western literature – Sherlock Holmes, Three Musketeers – or stories concerning non-Russian nationalities in the Soviet Union. This kind of literature was a reminder that Marxism was an international movement, even within the Soviet Union.

The Jewish Collective Farm (1931), pictured above, features Yasha, a young Jewish boy who works hard for the local sanitary commission. His productively and his tractor-driving prowess made him a local hero. He dreams, too, of joining the ranks of the peasants (which Jews were not allowed to do under the Tsarist regime). His reward is growing the best apples and cucumbers in the oblast.

Below is an image from The Millionth Lenin, by Lev Zilov, in which two peasant boys from India participate in an uprising against the Raj. From there, they have various adventures as they make their way to the Soviet Union.

Like Yasha, children were encouraged to be resourceful in Soviet literature. In Chimpanzee and Marmoset, readers are shown how to make the toy animals of the title using twisted rags.