A last gasp for the radical feminist and labour movements of the 1960s and 70s.

As a ratio of surplus labour to necessary labour, as Marx explains in Capital, the rate of surplus value equals the rate of exploitation, “an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour-power by capital.” Thus, the working class produces all the value in society; and yet, under capitalism, they receive only a fraction of this value back in the form of wages. The profit that powers capitalism forward is, therefore, the unpaid labour of the working class.

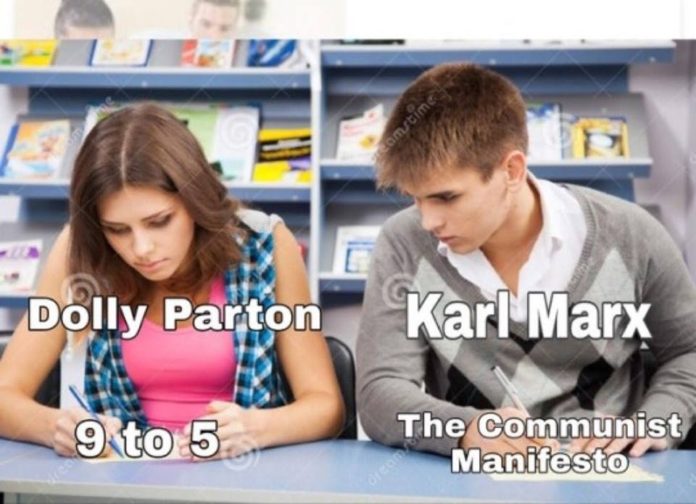

Or as Dolly Parton sings in the workers anthem and theme song to 9 to 5: “It’s a rich man’s game no matter what they call it / And you spend your life putting money in his wallet,”

This elegant distillation of Marx’s theory of surplus value features on the country icon’s 23rd album Odd Jobs, a long play record that includes a cover of American Communist Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” and the proletarian pean “Sing for the Common Man”. Sample lyric: You know the working man/ He builds what others plan/ So, everyone of us should sing his story… He paid for the song with the sweat of his brow.”

Released within weeks of Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, the workplace comedy 9 to 5 countered the coming liberalisation of labour laws with a radical set of reforms, including equal salaries for equal job levels and flexible work arrangements that allow workers to choose their own working hours and share jobs. Other initiatives, such as on-site office childcare and a drug counselling programme, mirror labour innovations of the early Soviet Union.

A last gasp for the radical feminist and labour movements of the 1960s and 70s, the film was conceived by Jane Fonda in tribute to the work of her friend, the anti-war and labour activist Karen Nussbaum. Actor-turned-producer Fonda initially envisaged a labour drama in the tradition of The Grapes of Wrath, or perhaps a dark fantasy after Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. But after years of being branded Hanoi Jane by her detractors, Fonda feared that a straight or realist depiction of women in the workplace would be dismissed as too feminist and too preachy.

Instead she drafted in Harold and Maude writer Colin Higgins and Robert Altman collaborator Patricia Resnick for a farcical comedy in which three working women – essayed by Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lily Tomlin – exact revenge on their “sexist egotistical lying hypocritical bigot” boss (Dabney Coleman).

Their solidarity simultaneously allows the women to topple the patrician bourgeois order and unpicks their own experiences of alienation. Returning to the workforce, Jane Fonda’s former housewife is so alienated from her own special human capacities (her “species-being”), that she cannot successfully use a photocopier.

Her colleagues are exploited in various and chilling ways. Lily Tomlin’s character has been passed over for promotion many times in favour of her male underlings. And she has watched her boss pass her ideas off as his own. She is, in common with the others, entirely alienated from the products of her labour.

Dolly Parton’s character is continually sexually harassed by her boss. In keeping with the fourth type of alienation outlined by Marx in Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Dolly is alienated from her colleagues because her boss, in addition to his grotesque violations, is spreading rumours that they are having a sexual affair.

“Our theory,” as Engels had it, “is not a dogma, but a guide to action.” Sure enough, the women find power in organising. After they kidnap their oppressor, they use his absence to make changes that “really count”. The boss isn’t killed outright. But he is “disappeared” to the Amazon.

Karl Marx did not use the phrase “9 to 5” in Capital. He did, however, note capitalism’s drive to extend the working day. Dictated by issues of productivity, possible proletarian discontent, and the calculation to extract the maximum amount of labour “… we find working days of many different lengths, of 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18 hours”, a dynamic expression of class conflict.

In other words: “It’s all taking and no giving/ They just use your mind/ And you never get the credit.”