The Limerick General Strike Against British Militarism – the Limerick Soviet – was the first and most significant event of a wave of soviets, general strikes and factory and farm occupations that swept across Ireland (predominantly in Munster) in the years 1919 to 1923.

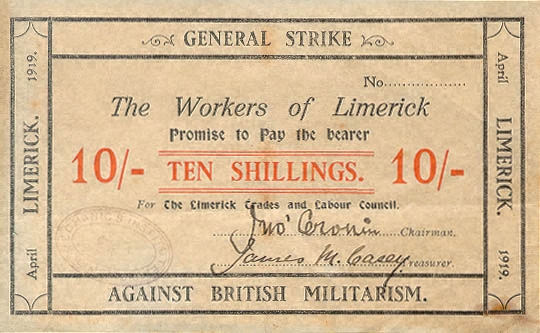

For two weeks in April 1919, the workers’ representatives controlled every facet of life in a city of forty thousand inhabitants. Supported by an Irish Republican Brotherhood/Sinn Féin regional network, they provided bread, butter, milk, vegetables, and other foodstuffs at controlled prices. Transport of goods and people around the city was controlled. They published ‘The Workers’ Bulletin’ and monitored the content of journalists’ reports sent from Limerick through the local Post Office. Some British trade unions refused strike pay because the strike was ‘political’ rather than ‘industrial’, so the Soviet printed its own currency.

The initial impulse for the strike had Republican roots. Robert Byrne was a Post Office Clerks’ delegate to the Trades Council and Number Two in a Limerick City battalion of the Irish Volunteers. He had been on hunger strike in jail and as he recuperated in Limerick Workhouse Hospital, he was killed in an IRA rescue attempt during which a policeman was shot dead. His massive funeral was a public show of strength and defiance by Republicans in the midwest.

Alarmed by the establishment of the First Dáil and the deaths of two policemen at Soloheadbeg a couple of months earlier, the British authorities declared Limerick a Special Military Area, requiring workers to obtain a military pass to cross the bridges on the Shannon to go to and from their workplaces.

Six hundred women, members of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) employed in Cleeves Condensed Milk factory voted to strike against the military restrictions. The Trades Council called out all fourteen thousand Limerick workers on strike. An ITGWU official, John Dowling, a Marxist, had been a close associate of Connolly and had led a series of major strikes in Limerick. Dowling and the union’s other Marxist organisers were a major factor in turning Munster into a hotbed of worker militancy during the years that followed.

The strike ended with a withdrawal of the detested permits system but the leaderships of both the Congress of Trade Unions and the Republican movement refused to support a national escalation. The workers and their socialist organisers continued on a militant path, with women workers at the vanguard of the movement. It is estimated that, in the succeeding years, there were hundreds of soviets, seizures, occupations and strikes, mainly across Munster.

Within a fortnight of the Soviet, creamery workers in counties Limerick and Tipperary went on strike. The ITGWU established the Munster Council of Action to coordinate activities. In all, there were thirty-seven strikes and lockouts across Limerick in 1919, almost twice as many as in the previous year. By December, the ITGWU had 7,500 members in forty-two branches in Limerick. In the following year it reached a peak of 7,800 members in forty-five branches. The Knocklong Soviet began on 16th May 1920 and lasted five days. It involved the occupation of twelve other satellite creameries. It was a carefully orchestrated effort by syndicalist union organisers to assert workers’ power and demonstrate that they could manage industrial enterprises. The workers repainted the entrance door from green to red, hoisted the red flag and the green-white-and-orange tricolour over the premises and hung out the memorable sign ‘We Make Butter Not Profit’.

In 1920, in the West of Ireland, there was a wave of agitation working to break up estates and big farms. The Republican Department of Home Affairs, under Countess Markievicz, saw them as ‘a grave danger threatening the foundations of the Republic’ and the newly established Sinn Féin courts and IRA police were used to snuff out the agitation.

April 1920 saw a two-day general strike in support of Republican hunger strikers. The rank and file took control and there were seizures, takeovers, soviets and red flags in scores of towns and villages. In 1921, a major economic recession provoked another strike wave and outbreak of soviets. The last throes of the wave of militancy was the Waterford farm labourers’ strike, as begun in May 1923. Evoking memories of the Russian Civil War, farmers formed units of ‘White Guards’ and the Government deployed a ‘Special Infantry Corps’ to support them.

From Limerick 1919 onwards, the geographical spread, duration, and level of violence of these struggles raises an important question in Irish history. Were there two revolutions and two civil wars at that time? Socialist-inspired workers first took on British state power in Ireland, then clashed repeatedly and violently with farmers as well as with Republican and Free State power. The latter were intent on suppressing class conflict in favour of unity, while seeking separation from Britain but, inevitably, sided with the big farmers and business.

Liam Cahill tells the full story of Limerick and the other soviets in his acclaimed Centenary Edition of ‘Forgotten Revolution [The Centenary Edition] The Limerick Soviet 1919’.