Marx’s preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy – in which he supposes that the economic structure, or base, of society is its “real basis, on which arises a legal and political superstructure” – is one of the most controversial aspects of Marxist theory. Many late 20th century Marxist theoreticians have questioned this reductive account of culture, as an entity sandwiched between ‘forces of production’ and the ‘relations of production’.

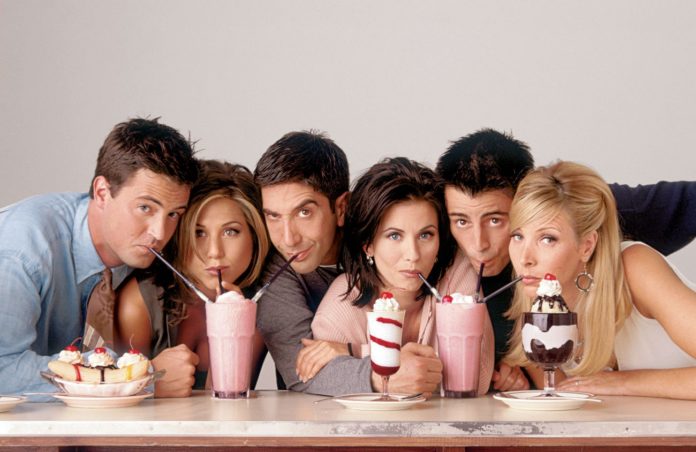

These same theoreticians were clearly never exposed to the post-Cold War triumphalism of Friends. Launched upon an unsuspecting world some three years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, this vile creation is emblematic of the sterility of late global capitalism. Unlike such contemporaneous competitors as Seinfeld – which plays the selfishness of its characters for laughs – Friends presents villainy as “relatable” virtue, psychopathy as endearing.

The US empire, standing unopposed at the end of twentieth century, no longer needed its propaganda to be heroic or even decent minded, when white, skinny, pretty, and base would sell just as easily.

In common with a great many American sitcoms, Friends is neither situational nor comedic. The Aristotelian purity and sense of entrapment that defines such great television comedies as Fawlty Towers gives way to multiple locales, each more plush and aspirational than the last.

Much has been made of the gap between the character’s earnings and their affluent Manhattan residences: as TV network CNBC cheerfully notes, with no sense of incongruity, the characters hold on to the apartment for a decade “despite various bouts of unemployment and low-paying jobs.” They thrive even though these low-paying gigs include infrequent acting work, waitressing, and a freelance masseuse business.

Much has also been written about the show’s painfully evident racism, fat-phobia, homophobia, and transphobia. (Only the latter seems to bother the show’s creators in contemporary interviews). Prepare to slap your thighs: Monica used to be fat! Ross’s ex-wife is a lesbian! It was all so hilarious that in a 2004 lawsuit Amaani Lyle, an assistant in the writers room, filed against the show for being exposed to the writers’ rape jokes and jeering “black ghetto talk.”

The former stars, who greedily negotiated more than $1 million for each episode of the final two seasons, were far from welcoming to outsiders, according to several supporting players, including Kathleen Turner and Helen Baxendale.

Their recent reunion – which was not the scripted episode fans demanded, but a fictional interview that glossed over Jennifer Aniston’s subsequent tabloid career and Matthew Perry’s battle with drug addiction – was a flimflam befitting the show’s 90s narrative and ideological nonchalance.

The avarice and preciousness of the cast, as was painfully evident in the whitewashed reunion, is equally entirely in keeping with the complacent yet callous imperialism that defines the show. This is a “comedy’ with catchphrases in lieu of jokes. Who needs a well-worked set-up or a bonne mot when endless repetitions of “Oh. My. God”, “Get a room”, “Could you BE more…”, and – oh yes, an actual cat-call: “How you doing?” – will suffice.

Global audiences in the 1990s, numbed by years of complex conflicts in Yugoslavia and Rwanda among other places, were quick to retreat into the cosy familiarity of hackneyed phrases, and the fantasy of watching straight and straight-haired people sitting on expensive pieces of furniture.

The characters are relentlessly cruel and narcissistic. To those characters who exist beyond the group, most notably the working class Janice, they are mean-spirited. But even within their own horrid group, they lie, cheat, and objectify. They endlessnessly peddle heteronormative and gender stereotypes. (Barbie dolls and childcare are not for boys.) Their romantic relationships are, without exception, abusive and controlling. They are often predatory.

At best, they are preening and selfish. Food, especially cheesecake, is prized before people. A heroic dive during a suspected shooting is for a sandwich, not a cadre.

At worst, they are malicious. Joey attempts to sabotage another young actor’s career with homophobic (ho ho) advice. Rachel attempts to ruin a sexual rival by encouraging her to shave her head. Ross hosts a funeral service for himself just to lap up the attention. Rachel jilts her fiance at the altar only to sleep with him when he becomes involved with her former best friend.

Robert De Niro is suing a former employee for, in part, watching 55 episodes of Friends in four days while on the clock. Never mind the clock.