James O’Brien discusses 1917, a democratic revolution.

A 100 years ago, imperialist war was consuming millions of lives in Europe and beyond. Millions more were being worn down by daily grind of poverty, even in the so-called advanced states, while the prospects for those in colonial possessions were bleak; the vast divergence in power between the European capitalist states in Europe and the pre-capitalist societies in Africa and Asia appeared unchallengeable.

Despite this, the world was about to change. As predicted by a generation of Marxists, the break would come in the weak link of the European powers: Russia. Insurgent democratic forces were to topple the tottering autocracy and inspire both working class revolts in the West and, within a generation, unstoppable anti-colonial movements, often led by Communists.

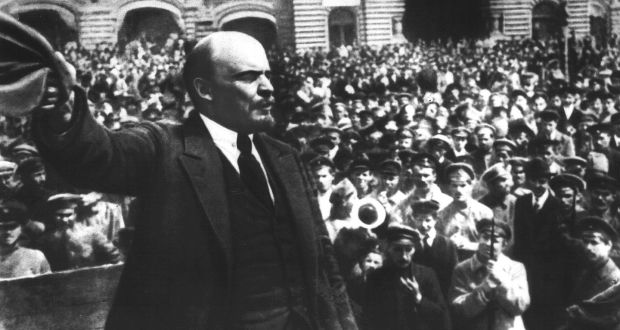

Although the movements did not reach any ultimate success in Western Europe, the Russian revolutionaries pushed their struggle to the end. Lenin and the Bolsheviks saw the struggle in Russia as primarily a democratic revolution against the feudal remnants of Tsarism, but, having studied the historical revolutions of England and France, the Bolsheviks also knew that the old aristocracy would gather their forces and strike back, ultimately seeking to destroy the revolutionary gains of the people.

This meant that they had to push the revolution right to the end: confiscate Church lands; abolish the aristocracy and entrust their land to the peasantry; enshrine the legal equality of women; end national chauvinism over the small nations; relegate religion to the realm of private conscience, and make representative government the norm.

The Bolsheviks were by no means the only democratic party in Russia, but they were the most radical. Whereas other socialist tendencies looked to the bourgeoisie to lead the struggle against Tsarism, the Bolsheviks identified the working class as the principal social force capable of carrying through the democratic revolution, as the ones who would not turn tail halfway as the German bourgeoisie had done in 1848.

Indeed, the record of the Provisional Russian Government, which ruled Russia between February and October 1917, illustrates how conservative the revolution would have been if the Bolsheviks had not taken power. During this period, there was no land reform, the war continued, and representative government was denied. The only change was a shuffling of pieces at the top: the Tsar was out, but the ruling class remained intact.

Given the international strength of the working class movement at the time, even the progressive bourgeoisie were wary of pushing revolution to its end. For who could say where the workers would stop?

The Bolsheviks, in contrast to most other socialist parties, placed their bets on the soviets, assemblies of workers organised out the factories and working class communities. Armed with two decades of labour organising and socialist agitation, the institutional strength of the working class was the decisive factor in pushing aside the timid Provisional Government and the essential force in withstanding the counter-revolutionaries from 1918 on.

The dominant contemporary Western view of the Bolsheviks is that of conspiratorial jacobins who diverted or deceived a popular movement to ensconce themselves atop a new authoritarian regime. But this loses sight of their role as the radical democrats of Revolutionary Russia: the party that pushed for workers to lead the revolution rather than the bourgeoisie.

Reimagine for modern times the Bolshevik strategy of connecting the democratic struggle with our ultimate socialist goal.

In a country that spans two continents, it was simply not possible for a minuscule conspiratorial minority to pull the strings of millions of workers and peasants. The more plausible explanation is that the Bolsheviks were not only in the right place at the right time, but that they put themselves there by building up a mass political movement under the noses of the oppressive Tsarist State.

Much has changed in the century since 1917, not least because of 1917. If the collapse of the USSR has freed the ruling class, and the USA in particular, to return to the most brutal form of capitalism, then we could do worse than reimagine for modern times the Bolshevik strategy of connecting the democratic struggle with our ultimate socialist goal. It is the essential ingredient to winning mass support, without which the working class movement cannot possess the strength to implement its programme.

James O’Brien is an occasional author on The Spirit of Contradiction website.